Maybe the most moving piece here is "On The Rainy River," about a draftee's ambivalence about going, and how he decided to go: "I would go to war-I would kill and maybe die-because I was embarrassed not to." But so much else is so structurally coy that real effects are muted and disadvantaged: O'Brien is writing a book more about earnestness than about war, and the peekaboos of this isn't really me but of course it truly is serve no true purpose. Some of these stories/memoirs are very good in their starkness and factualness: the title piece, about what a foot soldier actually has on him (weights included) at any given time, lends a palpability that makes the emotional freight (fear, horror, guilt) correspond superbly. It's being called a novel, but it is more a hybrid: short-stories/essays/confessions about the Vietnam War-the subject that O'Brien reasonably comes back to with every book. Bobby has come back to Pittsburgh, tail between his legs, substitute teaching and picking up the odd acting job, and it is on one of those gigs, a low-budget horror film, that the couple reconnects, falling into their old comedic rhythms. The story least reliant on the supernatural may leave the most readers pining for a full-length treatment: “Bobby Conroy Comes Back from the Dead” reunites a funny but failed standup comedian with his equally funny ex-high school sweetheart Harriet, now married and a mother. “My Father’s Mask” is a surprisingly romantic piece about a small, clever family whose weekend in an inherited country place involves masks, time travel and betrayal. It’s Morris who removes the problem for the big brother he loves, guaranteeing perpetual guilt and anxiety for Nolan. Eddie and Nolan spend their time in accepted slacker activities until Eddie, whose home life is rough, starts pushing the edges, leading to real mischief, a big problem for Nolan who would rather stay within the law. Morris, whose problems dominate but don’t completely derail his family’s life, spends the bulk of his time in the basement creating intricate worlds out of boxes. One of the longest and best, “Voluntary Committal,” is about Nolan, a guilty, anxious high-school student, Morris, his possibly autistic or perhaps just congenitally strange little brother, and Eddie, Nolan’s wild but charming friend.

In addition to the touches of the supernatural, some heavy, some light, the stories are largely united by Hill’s mastery of teenaged-male guilt and anxiety, unrelieved by garage-band success or ambition.

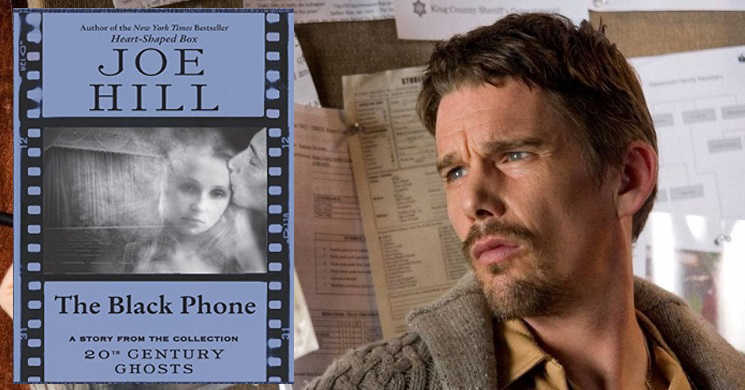

Published in a number of magazines from 2001 to the present, most of the stories display the unself-conscious dash that made Hill’s novel an intelligent pleasure. A collection of pleasantly creepy stories follows Hill’s debut novel ( Heart Shaped Box, 2007).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)